I had never been more active creatively then when I was posting and promoting my art on Instagram. While under the influence of the dopamine and endorphin buzz of virtual validation, I was churning out content more than ever. Content is not to be confounded with work. Much, but not all, of what I shared on Instagram would have simply been part of the brainstorming process of something more thought out had I not felt the unconscious pressure to keep up the rapid cycle of idea-create-feedback.

To be rewarded as an artist on Instagram is the fleeting validation of likes, hearts, and increased exposure. For artists, exposure is akin to the experience promised to unpaid interns; both are imaginary currencies that we’ve been told, even forced, to invest in in order to succeed.

In its defense, Instagram provides us with what we all crave deep down: attention and validation. Without the reverberation of stranger’s feedback – whether in the form of direct contact, or more passively, via ‘likes’ and heart emojis, we would simply be screaming into the void in search of an echo.

I know I’m not the first to admit that my relationship with Instagram is an ambivalent one. I know can count on Instagram for the diffusion of these very words. And yet, we are faced with mounting evidence that it is making us more narcissistic, eroding our self-esteem, and deteriorating our attention-spans. What started as a photo sharing platform and networking tool rapidly morphed into a slanted, commercialized popularity contest. Instagram has not only monopolized our attention, but our collective appraisal of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art.

“Instagram has not only monopolized our attention, but our collective appraisal of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art.”

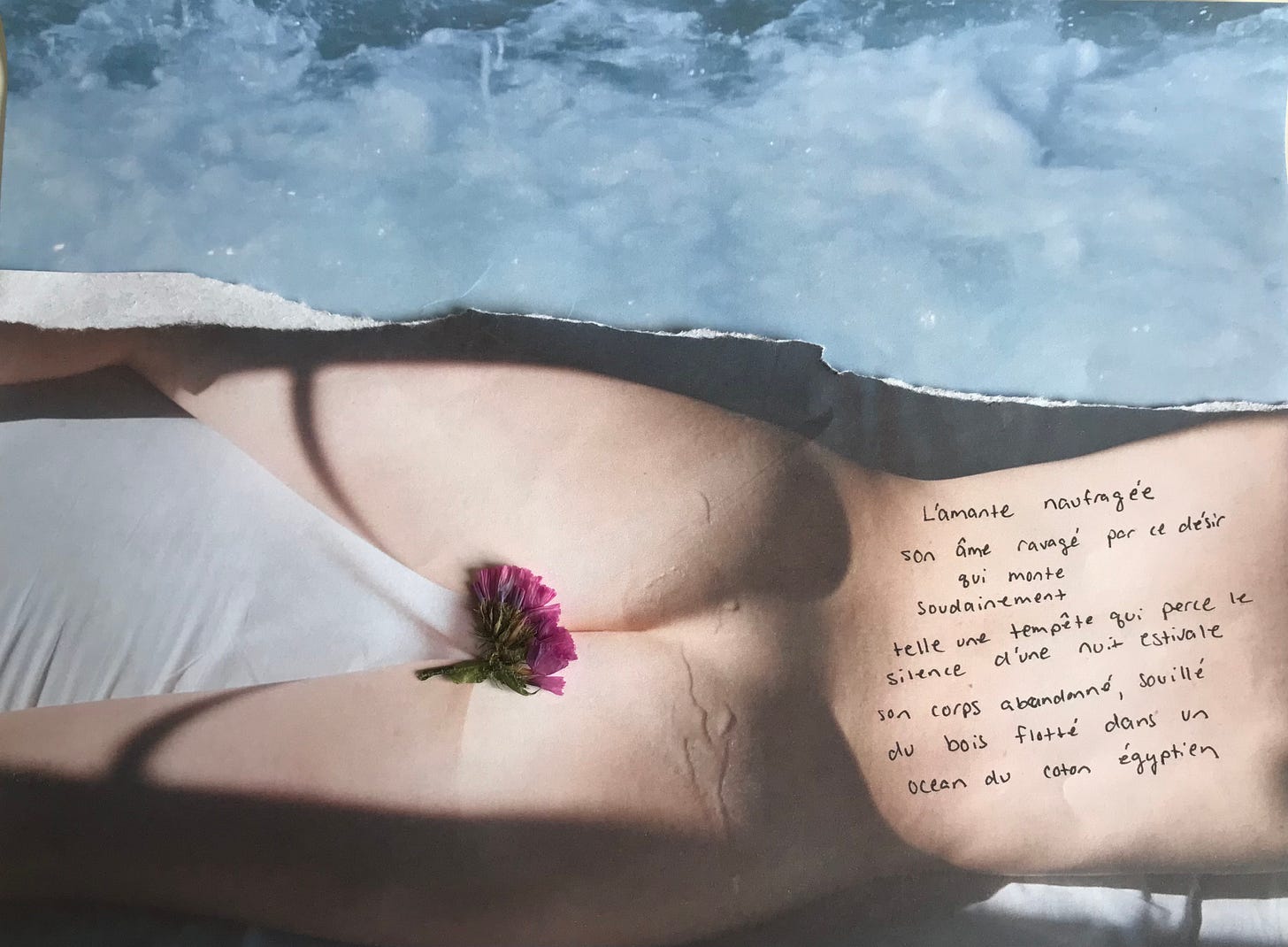

The integrity of our art, much like our mental health, is suffering. Still, we continuously perpetuate the belief that only way to exist in the world as an artist, is not only to keep an Instagram profile, but to foster and maintain an ‘audience.’ The result is the commercialization, and thus homogenization, of art: a continuous output of trending themes and personal brands. The instafamous artists are social media celebrities whose artistic work is merely the symbolic representation of their life stories.

Rupi Kaur first gained popularity on Instagram following the removal of a photo of her with her period. Supporters lauded her short-form poems on themes such as womanhood and trauma, spawning the creation of a new title: the InstaPoet. According to Kaur, who now tours the world and published several books, poetry is “like running a business.”

Indeed, when artists become entrepreneurs, they must continuously produce content at a rhythm which clashes with the time needed for craftmanship and artistic process. Of the art I shared, it was the prettier, easily digestible posts that most people responded to, regardless of how little thought or time I put into them. One might conclude that artists such as Ms. Kaur are not capable of creating not only meaningful, but also well- crafted work.

However, writers, journalists, and artists alike must bend to the new rules of click-bait and an eight-second attention span or be obliterated. Kirsty Melville, Kaur’s publisher, says in defense of her simplistic style, ‘the medium of poetry reflects our age where short-form communication is something people find easier to digest or connect with.’ It should be cause for alarm that a writer’s own publisher accredits their success to being ‘easier to digest.’

Defenders of the new cohort of Instagram artists argue that current mediums and technological advances have always influenced art. They’re not wrong, but Instagram and (social media more largely) is different in that it imposes constraints on art itself. Art critic Drew Zeiba describes Instagram as, “a space bound by certain social, aesthetic, and user-agreement constraints, all of them prescribed either top-down by Instagram design or policy, or more amorphously by cliquish consensus among a segment of users, in turn shaping the kind of content that might be made and shared.”

In the current digital context, survival of the fittest is determined by likes, shares, and followers. Instagram lends itself to instant-gratification and instant feedback, which developers understand are powerful drivers of human behavior. At one point, my creativity was driven by instant gratification.

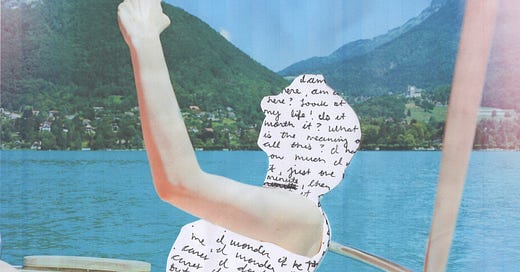

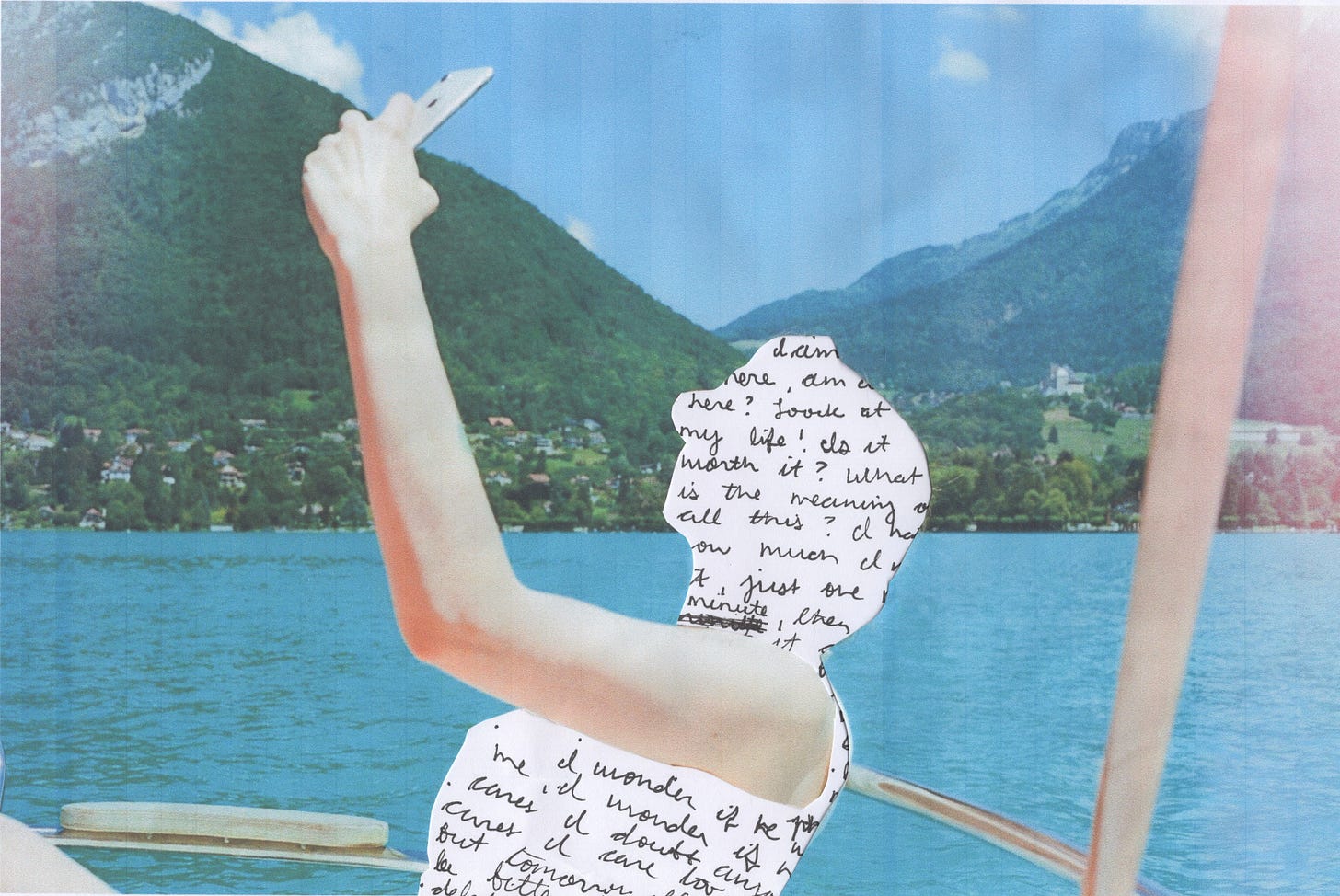

When I spent hours, even days writing poems and texts, often accompanied by photos or videos, I rushed to post them on Instagram as soon as possible in pursuit of that dopamine-hit. It didn’t take long to notice that that work (particularly texts) that lacked the flashy, punchy element that appealed to the algorithm was largely ignored.

I knew that likes were not an indicator of depth or artistic merit, and that the algorithm was biased, so why, then, did I feel hollow inside when I didn’t get the anticipated response? It is time we examine how Instagram’s reward system influences our art. The narcissistic self-promotion Instagram encourages (or even requires) amplified the decades old cult of personality to the point that it’s now embedded in our cultural bedrock.

“The narcissistic self-promotion Instagram encourages (or even requires) amplified the decades old cult of personality to the point that it’s now embedded in our cultural bedrock.”

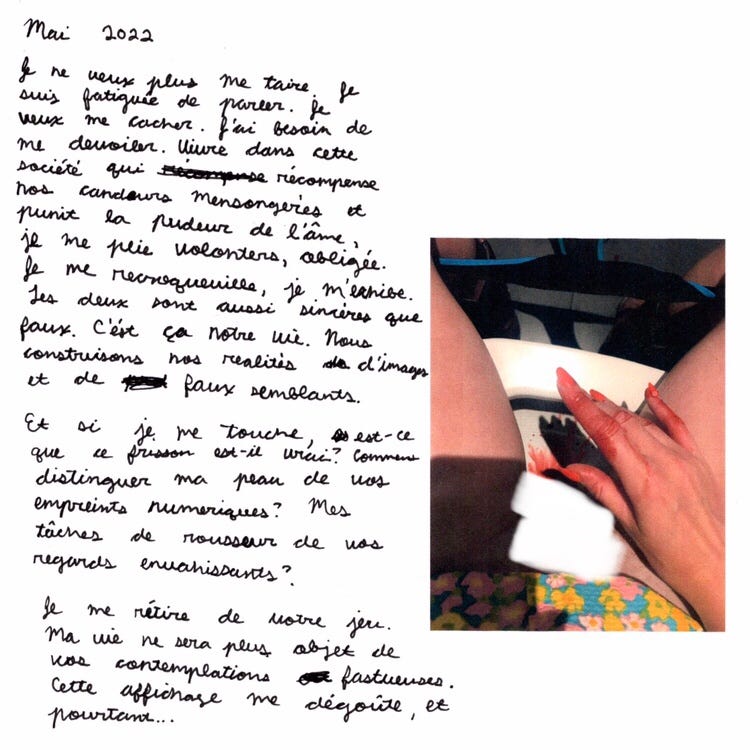

Writes Zeiba, “refusing to be an artist-as-public figure in the era of social media seems almost reckless—like willful career suppression, if not suicide.” On a platform containing billions of users, artists must go the extra mile (even if it means paying to promote posts) to stand out from the masses. I know one artist who used her image to promote her art, amassing over fifty-thousand followers. Eventually, her curated persona took precedent over her art, which increasingly melded into the Instagram mold. I made the mistake in believing that what worked for artists like her would necessarily work for me, believing that putting myself before my art was the game I had to play if I wanted to build an audience of potential readers.

At first, embracing myself so openly was freeing, and I enjoyed the sense of community. But it wasn’t long before the bold vulnerability I took refuge in and was celebrated for felt caricatural, and that, unsurprisingly, the erotic image I projected became the commodity. I wanted exposure, only to realize that I hated feeling exposed.

I wanted exposure, only to realize that I hated feeling exposed.

Given the work it takes to build an image and promote oneself, coupled with Instagram’s addictive nature and skewed value system, the inevitable pursuit of likes, comments, and shares can subtly influence our decision-making process when creating art, and depletes the cognitive resources necessary to learn, mature, and create.

Artists are baited into investing time and energy into Instagram under the guise of an evened playing field, with the promise of networking and marking opportunities while bypassing the gatekeeping of traditional establishments. According to painter Riad Miah, galleries increasingly turn to Instagram to find artists with large amounts of followers.

Are galleries and publishers strategically backing ‘Instafamous’ artists to cash in on their popularity, or does social media accentuate naturally occurring herd mentalities in regards to taste? I argue that both are true. We know that Instagram has changed radically since its inception, that it is owned by Meta (valued $340.67 billion as of October 2022), that the algorithm promotes certain posts and profiles, while masking others.

We know that its censorship policies disproportionately, and often unfairly, target women (especially those representing their own bodies). We also know that promotion, and even “followers” can be bought, so why do we continue to tout its supposed democratic virtues? What we are experiencing is a collective case of Stockholm Syndrome.

For several months now, I’ve more or less taken a leave of absence from Instagram. It occurred to me that I thoughtlessly gave away my art, my time, my attention, and more importantly, my self, to Zuckerberg’s dystopic digital empire, in exchange for the vague promise of exposure, success, and validation. In many ways, Instagram facilitated connections for me and provided opportunities for which I am grateful, and I don’t intend to invalidate the experiences of those for whom Instagram has been positive and beneficial.

Like in any toxic relationship, if there was nothing to gain, so many of us wouldn’t endure the daily tug-a-war as to whether to delete our accounts or not. We are admittedly disheartened by the world as seen through the Instagram lens. So why do we stick around? Stronger than the fear of missing out is our fear of the unknown. We’re so accustomed to our personal echo chambers that we fear the silence of real life. We’re so caught up in our digital hamster-wheels that we’re afraid of what might pass us by if we slow down. Is it too late to go back to the time when we sought out opportunities directly?

“Is it too late to go back to the time when we sought out opportunities directly?”

instead of passively waiting for opportunities to come to us as we scrutinize the number of likes our post gets, who watches our stories or who follows who? I don’t believe it is, which is why I am jumping off the hamster-wheel to reconnect with mediums of the past: blogs, newsletters, and magazine submissions, and old-fashioned pen and paper. It’s amazing what you observe when you aren’t bombarded with what everyone else is doing, and what ideas come to you when you turn off the constant chatter of advertisements. I don’t feel as though I’m missing anything, and even if I am, I’m okay with that.

Inspiring x💗

Amazing! Bravo 💋